A little more than a century ago, American families were asking some of the same questions we are asking today as they faced the influenza pandemic of 1918.The virus killed an estimated 50 million worldwide, leaving a legacy in homes all across America—but its imprint lingers on families too.

My family lost my 18-year-old-great-uncle to the pandemic, something that is regularly talked about at family gatherings. A close friend of my mother’s was only a few months old when her father succumbed to the 1918 pandemic, and her mother bore the weight of being a pandemic widow for the next seven decades. My mother and her friend told us stories of going to school in the 1920’s with small containers of camphor hung around their neck, as it was thought to help guard against virus. This probably explains the obsession this generation had with camphor canisters hung in closets.

But closets aren’t the only domestic spaces shaped by the 1918 pandemic.Our modern bathrooms and bedrooms trace back to this national public health crisis in ways big and small. Here are five elements of the modern home made ubiquitous by pandemic.

Bed frames were a simple change to understand. Not surprisingly, people were concerned about cleaning home surfaces. Wooden bed frames, headboards, and footboards were difficult to wash down. Iron and brass beds, however, were easy to clean with bleach and water, and then wipe clean and dry. So, wooden beds fell out of favor and iron and brass beds rose in popularity.

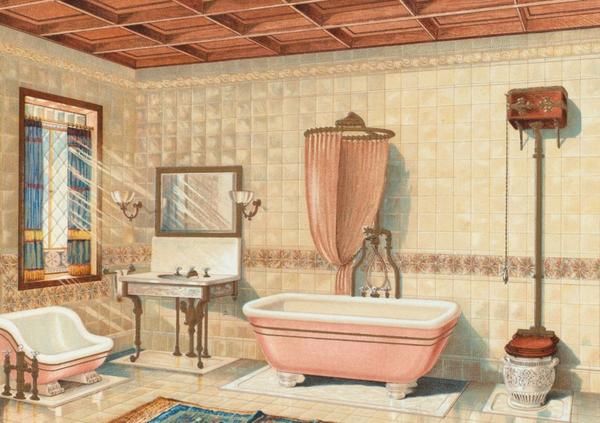

Up until the 1920’s,picturesque clawfoot tubs on legs were common. But, they were difficult to effectively wash, clean, and dry. Just think about all surfaces of those tubs—including the undersides and the sides against the walls, often wood wainscotting, and the wooden floors under them.After the pandemic, bathtubs were no longer freestanding but instead, built into alcoves with their edges sealed against the tiled wall on three sides.

The tiling on the wall alongside the bathtub rose to seven feet off the ground. There were some corner tubs, only against two walls, but the foot of those tubs was a finished porcelain surface that continued to the floor, with no crevices or joints to collect dirt.

The 1920’s bathroom commonly included bright white subway tiles with very thin grout lines, to a height of four feet off the ground, often with some thin, black accent tiles, or a band of accent pattern near the top of the tiled section. The white tiles simplified cleaning — and added a nice modernist aesthetic to boot.

Pedestal sinks became the norm, with a turned-down porcelain edge on all four sides. The rear of the pedestal sink was kept away from the fully tiled wall behind it, leaving enough room to clean both the tile and the rear of the pedestal sink.

If you have a 1920’s bathroom with a pedestal sink, look underneath it, as they come with a “birth certificate”—a metal stamp with the date of manufacture. Mine was fabricated on July 20, 1928, exactly 41 years before Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the surface of the moon.

And of course, no discussion of the home bathroom would complete without alighting upon the toilet. Toilet design was in evolutionary mode already, and the pandemic was the final death knell for the old-style wooden water tank mounted high up on the bathroom wall.

All toilets became the two-piece tank-and-bowl design we still commonly use in our homes today. Flushed out also were the unfinished wooden toilet seats, giving way to those highly polished black or white lacquered toilet seats that are easy to visibly keep clean.

Personally, I love the evolution of the American bathroom. Most of my 1928 white-subway-tile bathroom is still in original form — with the addition of a new high-efficiency toilet.

In this current pandemic, we are all spending a lot more time in our homes, using them in multiple ways, some for the first time.Our perspective on what we want from our homes is bound to change, if not in response to health and cleaning concerns, in terms of lifestyle. How will this impact how we design our homes in the 2020s?

Will we want more space or less stuff; more open design or a return to more segmented uses with separations between them?

Let’s pay attention over the next few years on how this changes how our homes look.