William Howard Taft was used to loss.

After 1909, he lost best friend Teddy Roosevelt in a political squabble.

In 1912, he lost re-election to the White House.

And, in 1913, he lost something else, something unexpected, something so unusual it was reported with surprise in the New York Times.

He lost weight.

A lot of it.

But there was more to the story.

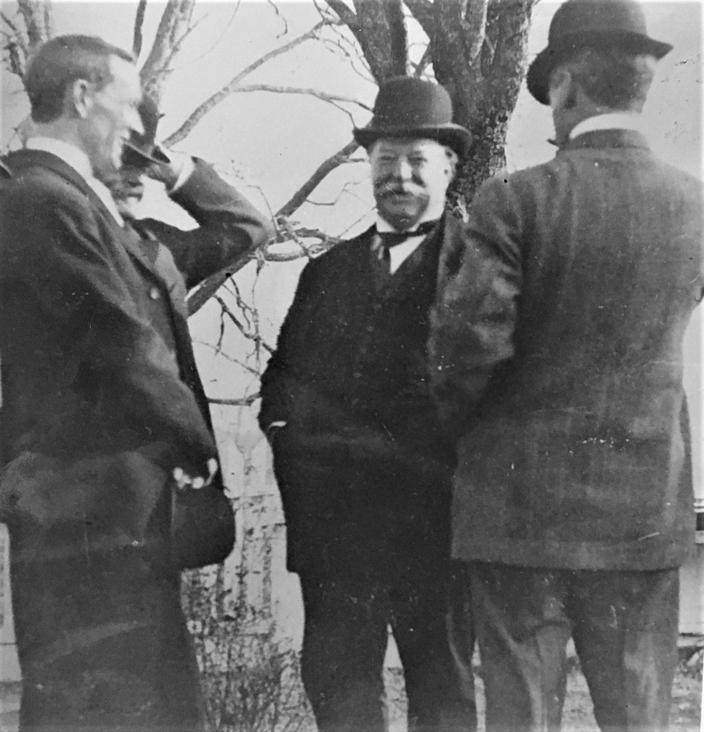

Most of us know that Taft was the largest man to serve in the White House. When he concluded his single term a little more than a century ago, he was a portly 340 pounds sometimes estimated 350 pounds.

If you want comparisons, that’s the weight of three James Madisons.

His size contributed to the Taft legend.

Once as governor-general of the Philippines, Taft sent a telegram to Washington that read, “Went on a horse ride today; feeling good.”

Secretary of War Elihu Root responded, “How's the horse?”

Although the story that he once got stuck in the White House bath tub might be an exaggeration, there was a bath tub specially made for him and a photo of it exists. The picture shows four workmen comfortably seated within its wading pool-sized walls.

Taft knew his weight was a health risk and he began trying to control it in 1904, several years before winning the presidency.

He contacted British doctor Nathaniel E. Yorke-Davies, a man known for diet success, which he proved with Taft. In April 1905, six months after he first wrote to the doctor and undertook his regimen, Taft had lost 60 pounds.

There were, however, challenges. Taft was “continuously hungry,” he confessed to the doctor.

The diet began to be ignored and Taft regained weight. He quit writing to the doctor, who sought out Taft family members to find out what was going on.

He was told Big Bill was becoming Bigger Bill.

By the time Taft was inaugurated as president in 1909, he regained all he had lost, and picked up a pound or two, now weighing 354 pounds.

He lost re-election 1912 and we can imagine it was a sad day in March 1913 when the man sometimes known as "Big Dub" gave Woodrow Wilson the door key to the Oval Office and, as The New York Times reported it, "started to his 'Southern Home' in Augusta, Ga., there to rest and recuperate."

But that spring trip to our town a century ago inspired something else: a big change in the big man and what could probably be called the most successful weight loss program of any other president.

Over the last nine months of 1913, Taft lost 70 pounds. This was achieved under the direction of another doctor, but rivaled the success of his earlier effort.

When reporters spotted him during a December 1913 visit to New York, they hardly recognized him.

"Mr. Taft," a New York Times reporter inquired politely, "would it be out of place to ask you how much flesh you have lost since you left the White House?"

"Not at all," Taft answered in a Dec. 12, 1913, interview. "When I left Washington for Augusta, I weighed exactly 340 pounds. This morning I weighed myself again and I tipped the scale at exactly 270.8 pounds … I certainly feel fit and fine as a result of it."

The reporter asked how he did it, and this is how the former president described his weight loss plan:

"I have dropped potatoes entirely from my bill of fare, and also bread in all forms. Pork is also tabooed, as well as other meats in which there is a large percentage of fat. All the vegetables except potatoes are permitted, and of meats, that of all fowls is permitted. In the fish line I abstain from salmon and bluefish, which are the fat members of the fish family. I am also careful not to drink more than two glasses of water at each meal. I abstain from wines and liquors of all kinds, as well as tobacco in every form."

Taft even told the reporter that he and Mrs. Taft planned to head back to Augusta in April for a visit to their "home folks" in that Southern city.

"Augusta," the Times added, "held a very dear place in his affections."

When Taft died in 1930, he’d done a pretty good job of keeping his weight at 280 pounds … light for him, but for the rest of us, the same as two Andrew Jacksons.

Bill Kirby has reported, photographed and commented on life in Augusta and Georgia for 45 years.